The Garland by Hyacinth Schukis

Hyacinth Schukis

The Garland is a beautifully made book object, with creamy matte cover stock, and russet ink floral motif framing the front and back covers. My copy has some dirt in its gutter (it’s been bouncing around with me since I first encountered it tabling next to its author at AWP) but is no less beautiful for that. Inside are black and white photographs, facsimiles of pages from Loeb translations or guides to ancient Greek temple architecture, postcards, handwriting, and short lyrical prose entries.

The book description reads:

THE GARLAND is an archaeological love story / a story about falling in love with archaeology.

It weaves together prose fragments of an education in Ancient Greek culture, a lesbian infatuation with one ancient statue, and a few years of gender-fuckery. Within are meditations on long teen-girlhood, joining the Sappho fandom, t4t love and anti-memoir transition, burial and unburial, queer museum visits, study-abroad heartbreak, products from your local mall, purloined favorite textbook pages, and plenty of Mediterranean sunsets.

The Garland articulates the eroticism of looking at art, which we worship in the tantalizingly inadequate pursuits of study and criticism (see also: AV Marraccini’s We the Parasites). We develop around the art that affects us. Schukis models the ongoing process of becoming as they oscillate through academia, art, archaeology, love, searching for a felicitous form. Arriving at this hybrid text as an artifact of that search.

The Garland is a deceptively simple book. Or rather, I shouldn’t accuse its author of deception. Why hedge around simplicity? Simply put: art, like love, can wound us. In fact, when it does wound us, for the first time, or as if for the first time, we regard it not like critics but like applied phenomenologists (that is, as poets). We become acolytes of the beloved thing, returning masochistically to be wounded again and again.

In The Garland, the erotics of looking back at the cultural production of ancient Greece is quite literal, embodied in a love story between the narrator and Phrasikleia. Schukis makes it clear that what they have isn’t milquetoast appreciation, but genuine ardor:

PHRASIKLEA IS ADORED

A fourth, maybe fifth trip to see her—we look a bit the same. Our sandal straps and floor length gowns match at least. I wear a black jumper that falls in drapes around my hips, black Tevas. She wears the same peplos she always does, unwatched, untouched, stiff up there. We’d be the same height were it not for her pedestal. I wonder what she weighs. I wonder if she is cool or warm, rough or smooth, what she sees here and what she remembers, if her lips are hard. I pace around her slowly in the peachy and dim museum vestibule. I don’t have a notebook or a camera beside me on this trip. I just want to see her. No pretenses. Sweat gathers on my brow, under my arms, on my legs. On my umpteenth rotation around her form, not unobserved by the guards even as they change what foot their weight rests on or float between rooms, I notice a little sweat on her brow too, or perhaps a glint in the marble. When we’re alone I stop to look into her eyes, mutter her last words for her, more from memory than from the inscription. sēma phrasikleias, (sign of phrasikleia) kore keklesomai (maiden I shall always be) aiei anti gamo, (forever against marriage) para teon tuoto, (by the gods this) lachos onoma (name is my lot)… It’s present, but effaced, under her feet. I get warm from love, spirit, or embarrassment.

There is romance here, but Schukis also pushes back against simplistic romanticism. To wit, their metacommentary on FRAGMENT 31: A LOVE STORY:

The first translation of Sappho I read was the Mary Barnard one from the fifties. I believe it is still the most popular, though Anne Carson’s sidles close. I learn in a talk by Kay Gabriel that Barnard went to Reed College in my hometown of Portland and that she studied under the Fascist poet Ezra Pound, who really haunts me, especially when ignored. (No neoclassical exercise is pure). Gabriel writes that Pound’s aesthetics of the fragment has gone on to immensely influence the style of Greek to English translations, piecing up what is in fact more whole.

Impurity, in this context, connotes the aesthetic and political consequences of the way we arrive to a field (like classics, archaeology, or poetry). It is never a tabula rasa, so engaging with a field means engaging with the ways it has been used in service of, in this example, fascism. But taken another way, impurity can also refer formal hybridity—the Lex ads and t shots that would not have been admissible in THE BOOK ABOUT HER I DIDN’T WRITE, the outline and bibliography of which are included in The Garland, but which are admissible, essential, to the book Schukis did write.

I’m such a sucker for the book written in lieu of another book (e.g. Renee Gladman’s To After That (TOAF)) or books written as a sort of side effect of writing another book (e.g. Trish Salah’s Lyric Sexology Vol. 1 which in some ways forms the reverse of her dissertation). About Schukis’s unwritten book, they write:

I hope someday I’ll be ready to tell the story of the day I knew I couldn’t write the first book that I drafted up about her. When I was young I wanted History to let me bitterly circle where I thought she wasn’t seen, underline who I thought didn’t see her. I couldn’t look the other way.

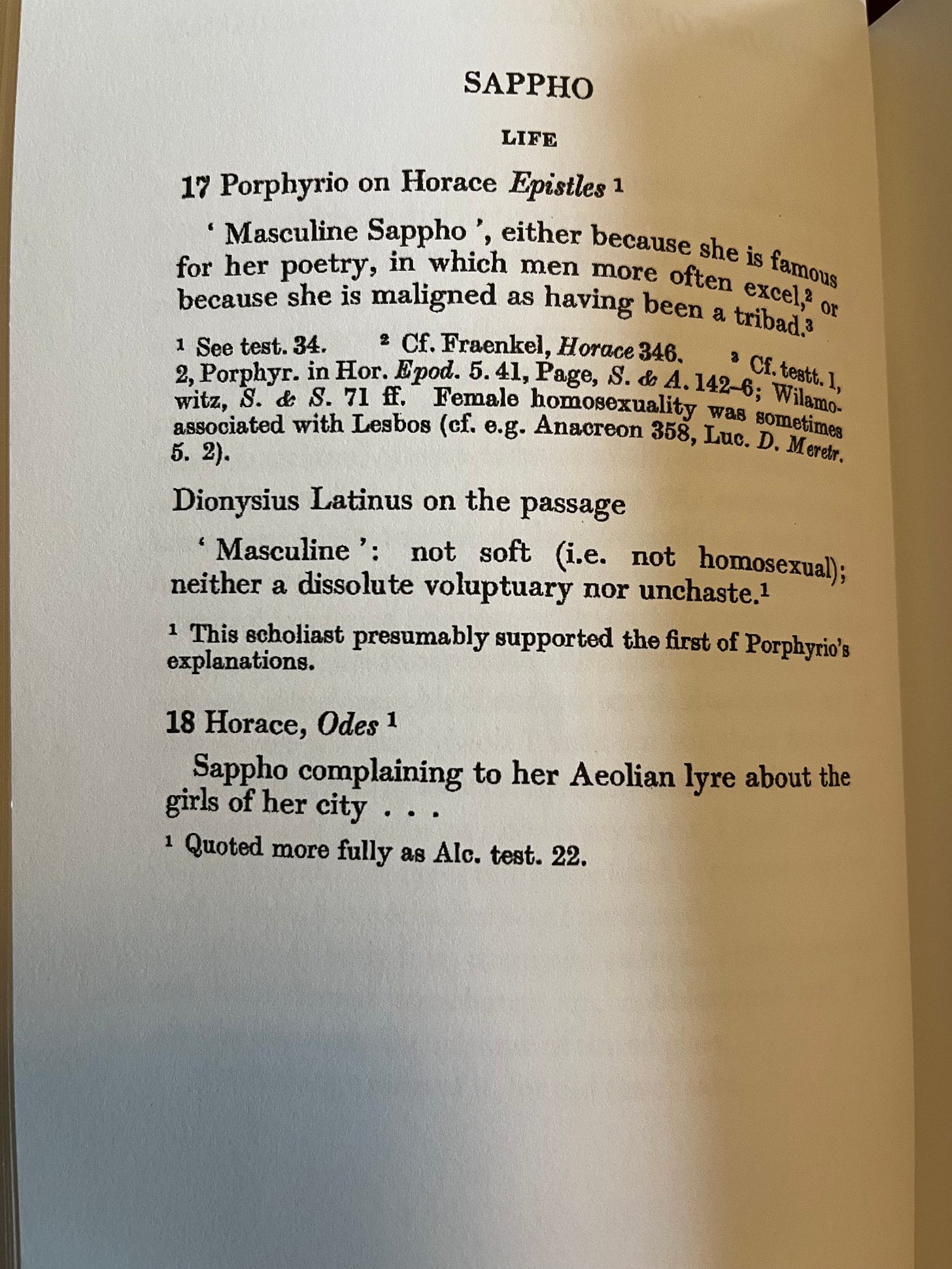

There’s so much texture and visual information in handwriting and drawing, as well as in reproductions of pages from books. If it were simply that Schukis wanted to reproduce a certain text, they would have quoted it, but treating text as image in these instances shows the typeface and design, which put the text-image in context, and give other visual information (like the slight blur from a text that has been frequently reprinted using the same plates). This puts me in mind of Susan Howe, whose books are enriched by this process of visual quotation.

I’ve been working on the introduction of my next book, which is about the pleasures of reading. It has an emergent motif of the snake. Daydreaming associatively, I wonder whether it ought to have a snakes and ladders structure, in which the ladders are willed ascent and descent (like the archaeologist into their dig), and the snakes are the pang (and fang) of falling in love. Here in the realm of the symbolic snake is the ouroboros. The image is of a snake eating its own tail, but what does it signify?

I would argue that its long career as a hermetic image is because it embodies a synthesis of any number of apparent dichotomies: yoni / lingam, beginning / end, self /other. How a symbol signifies for an author depends on how she uses it. I lift the ouroboros and wear it for a flower crown, a garland, albeit one whose serpentine flowers are ready to writhe off in answer to The Garland’s Tiresian moments or to twine around a the rod of Asclepius, symbol of healing, in sympathy with the chronic illness which appears.

In KERAMEIKOS, Schukis writes, “Statue bases and column bases are distinguishable by their circular holes that collect water in the rain, now a womb for microbiology and no longer the tomb.” As I complete The Garland, wanting to write about it, I loop back to the beginning. One of the initial images, a black and white photograph of pitted stone, with a circular depression, now becomes clear. Schukis circles around their topics, revisiting and renewing the initial wound, but I love that they first give this statue base without explanation.

Another reason The Garland is aptly named is on account of the daisy chains of philhellenic queerness that extends through time (in the form of lineage) and space (in the form of contemporary affinities, like Sophia Dahlin’s sapphics, or Kay Gabriel, whom Schukis cites). Having spent 2022 reading Robert Duncan’s HD Book aloud in a small group, this sense of lineage is close at hand.

The beloved teacher appears and reappears, as do the beloved texts. Or to be more specific, beloved books. I find it interesting that Schukis takes pains to note that, for instance, their Loeb edition of Sappho’s fragments, “…does not follow either currently accepted standard treatment” and yet it is the one they use. Because it is ready-to-hand or because it is the beloved book?

I think the latter. Books, like bodies, bear the physical traces of their use over time. The individual book, in its status as a beloved object, comes to exist in contradiction to its status as one among many identical units in an edition. By means of use (love), the reproduction attains its individuality, joins Phrasikleia, broken out of the anonymous chorus of kore figures. Not an example of the archaic smile, about which Schukis writes:

In her time statues don’t know how to scream or cry or even rest their faces. Their eyes are always activated, muscles engaged, and their lips always upturned. Under her smile could be anything: the relief of dying, or the sadness, or something more complicated. We cannot know.

but an instance of the beloved’s smile.